Since August 2022, Bendix Hagedorn has joined the Institute of Theoretical Astrophysics as new Ph.D. fellow in the Cosmology and Extragalactic Astronomy research group.

– "I am from Germany where I got a bachelor’s degree in physics (University of Hamburg) and a master’s in astrophysics (Ludwig-Maximilians-Universität Munich)", Bendix begins.

Transitioning from simulation to observations

During his master’s project, Bendix studied the evolution of galaxies in cosmological simulations.

– "I was particularly interested in the galactic gas component, how it cools to form stars, and how the radiation emitted by those stars in turn affects the gas", he tells us.

Since cosmological simulations need to cover such a large volume, they cannot resolve the comparatively small scales on which many of these physical processes happen. To fill this gap, physically or empirically motivated ‘sub-grid’ models are necessary.

– "I tested a model designed to track the evolution of hydrogen and helium-based molecules in non-equilibrium with a chemical network and use this information to improve the prescriptions for cooling and feedback effects", explains Bendix.

– "Here at ITA I am again studying galaxy evolution, but now from the observer’s side, which is new and exciting territory for me!", he adds.

Looking into the baryon cycle

– What is the main question of your study?

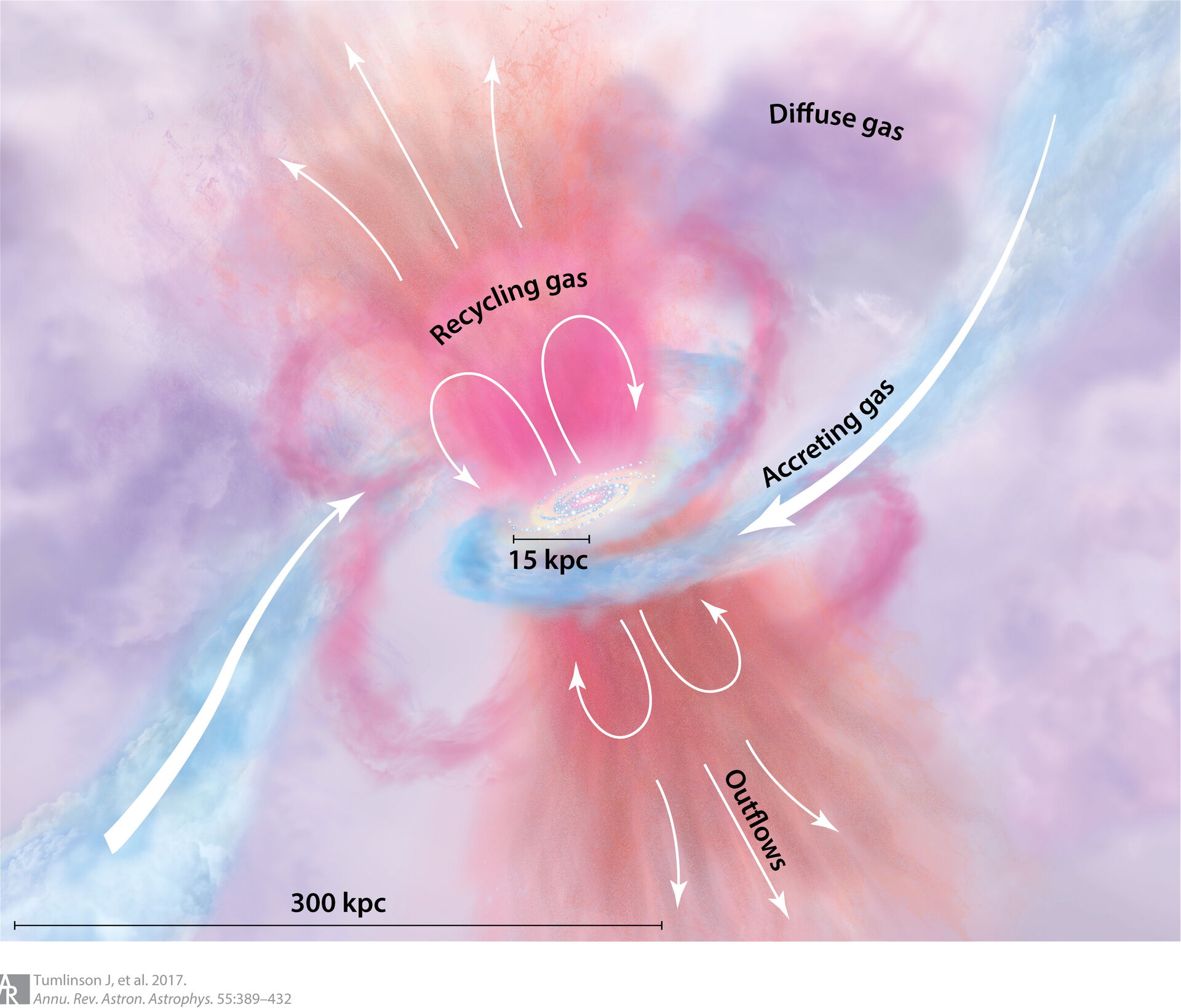

– The focus of my research will be on the motion of gas into and out of galaxies, a phenomenon called the ‘baryon cycle’.

A galaxy can only form stars if it has enough gas present under specific conditions. This reservoir can be depleted by energetic feedback from star formation or black hole accretion which can drive gas into the outskirts of a galaxy or even all the way out into intergalactic space.

– "Studying these ‘outflows’ helps us understand the evolution of galaxies across cosmic time", he adds.

Bendix will look into data from large galaxy surveys for a statistical analysis of galactic outflows and their connection to the galaxies intrinsic and environmental properties.

– "Basically, I want to understand in what kinds of galaxies and environments outflows show up and why", he tells.

Screening hundreds of thousands of galaxies

To this aim he will be using some archival data of local low-redshift galaxies from the Sloan Digital Sky Survey (SDSS) and some observations of higher redshift galaxies from the upcoming Multi-Object Optical and Near-Infrared Spectrograph (MOONS) at ESO’s Very Large Telescope in Chile. Both datasets contain spatially integrated optical spectra of galaxies.

– How is your approach?

– "Since the objects are not spatially resolved I have to extract the information about the motion of gas in the galaxy from the shape of their spectra", adds Bendix.

The gas emits light at specific wavelengths that shows up as narrow peaks or ‘lines’ in the spectrum. The shape of these lines is determined by the kinematics of the gas via the Doppler effect.

– "I can fit a curve to the emission line and see if it is consistent with the circular motion you would expect in an undisturbed galaxy or if there are high velocity components, that might be outflows", he explains.

– "Because of the large number of galaxies I deal with (~800 from SDSS and hundreds of thousands from MOONS), It is impossible to do the fitting process by hand for each and every one. Instead, I am developing an analysis tool that can automatically choose an appropriate fitting method for the lines and determine the presence of possible outflows", he concludes.

Towards the understanding of the Universe, breadcrumb after breadcrumb

– What fascinates you about your research?

– "I just think galaxies are really, really, cool! I mean have you seen pictures? Who wouldn’t want to know more about those things?", confesses Bendix.

– "The question ‘how does the universe work?’ just seems like one that needs answering. And while it may not be very useful in a practical sense, maybe it can give us some perspective?", he continues.

– What are the challenges in your field?

– "The biggest challenge for me, and undoubtedly for many astronomers, is that we are so limited in what we can actually see of the universe. I can’t fly over and look at a galaxy close up or even just look at it from a different angle. Nor do I live long enough to see it evolve over time", he says.

"It’s like following a trail of breadcrumbs left by billions of people except you get only one breadcrumb per person and are still expected to figure out where they all came from and where they are headed"

– But it makes for an interesting challenge and it’s fascinating what crazy techniques people come up with to extract new information from these proverbial breadcrumbs, Bendix continues.

In love with Norway

– What brought you to Oslo?

– "Primarily, I came to Oslo because the project sounded interesting. But I didn’t need much convincing to move to Norway. I have been here on holiday a couple of times, mostly for hiking trips, and I liked what I saw!", says Bendix thrilled.

– What is your experience at ITA so far?

– "Everyone at the Institute has been super nice and I really enjoy the atmosphere. Of course, there were some cultural differences and bureaucratic oddities to deal with in moving here but nothing I didn’t expect", he confesses.

– "All in all, it has been a pretty smooth start for me. Also, everyone and their grandmother seems to be into bouldering in this city, which has been very helpful in making friends!", says Bendix.

– What do you expect from this experience?

– "One thing I’m fairly certain about is that there are a lot of new things to learn, so I doubt it will ever be boring for long".