The full master thesis is published in University of Oslo's research archive, DUO.

An infographic also provides a quick overview of the results.

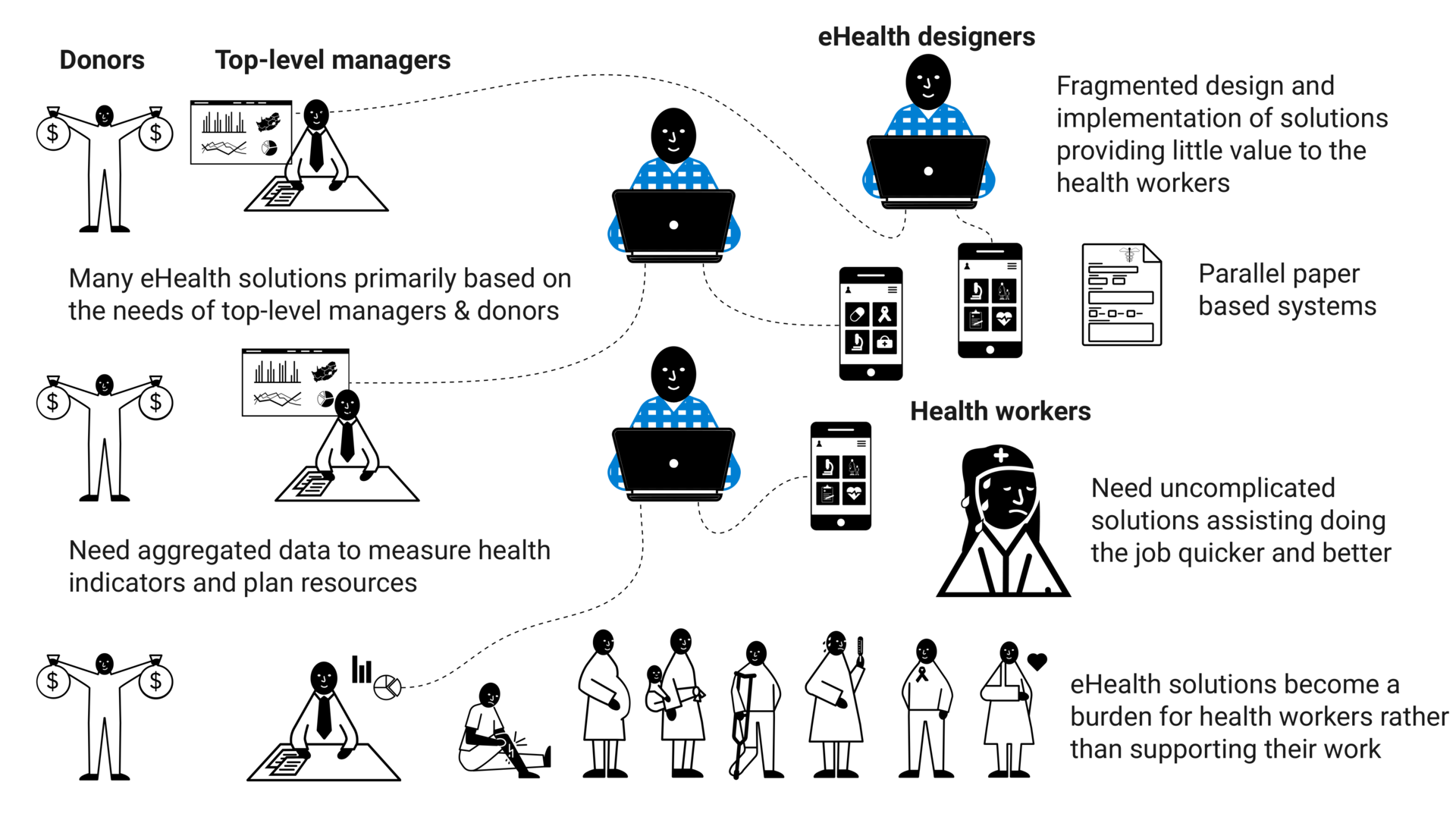

The real world problem

Digital solutions are increasingly important in healthcare delivery in LMICs, but they often fail due to a disconnect between how they were designed and how they are used in the real world. One common challenge is that healthcare workers in LMICs, who are already burdened with heavy workloads, are given solutions that add to their workload. As a result, healthcare workers are unable or unwilling to use the provided system. This may be due to excessive data collection requirements, the simultaneous deployment of multiple systems, or the need to use both paper-based and digital systems.

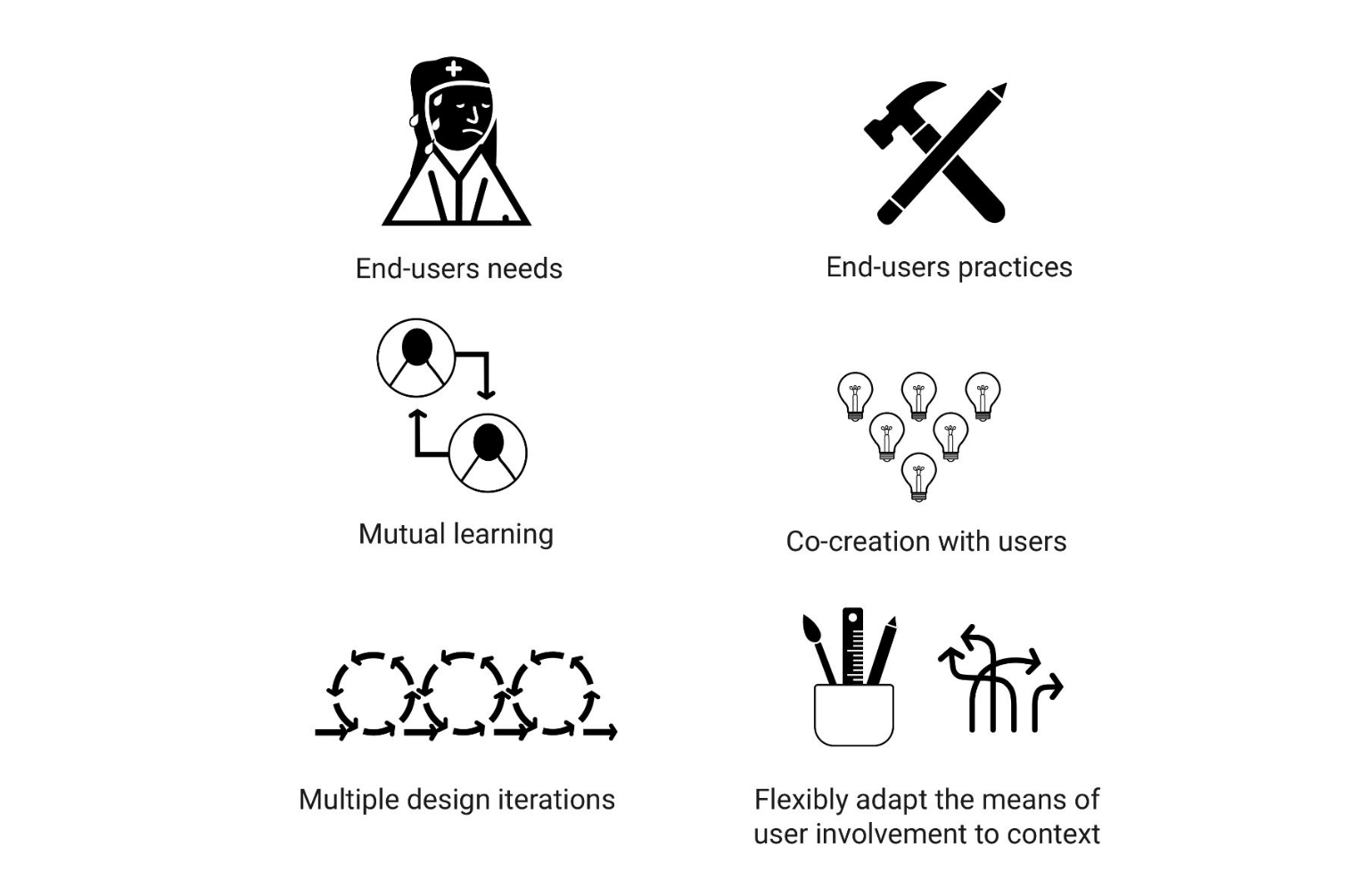

User involvement during design

Limited user involvement during the design of eHealth solutions is argued by many to be a significant factor contributing to failed implementation of eHealth solutions. Better involvement of healthcare workers in the design process can lead to a better fit between digital solutions and healthcare workers practices, as well as empower healthcare workers.

Designing digital solutions is a creative process where designers use various tools, techniques, and methods to involve users. These approaches are not rigidly standardized but need to be flexibly adapted to the design context. The field has developed an array of conventional means to involve users for various purposes, such as understanding their needs and practices, facilitating technology learning, and encouraging creative contributions through iterative design.

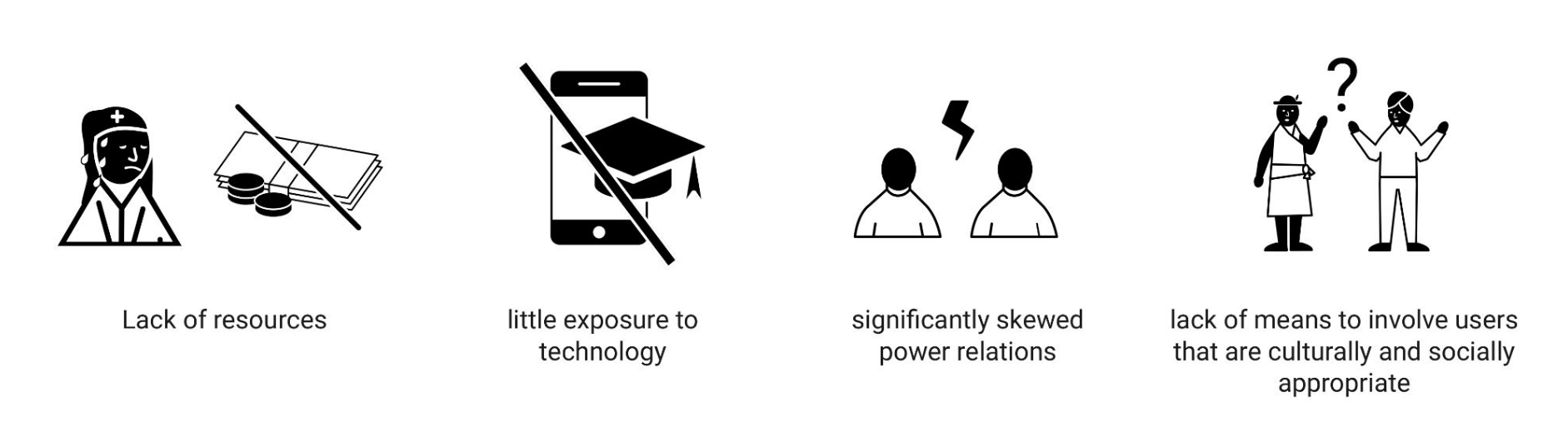

Challenges of involving users in LMICs

Despite the recognized importance of user involvement in creating usable and relevant eHealth solutions, practitioners in LMICs encounter numerous complex challenges. These challenges include limited resources, low IT literacy, unequal power dynamics, and a lack of culturally and socially appropriate means of involving users. However, the interplay between these issues, their extent, and potential solutions remain largely unclear.

Research approach

Opportunities to better involve users in LMICs have most often been explored from the perspective of foreign researchers than from the local eHealth designers that work in these contexts on a daily basis. This thesis examines user involvement opportunities in LMICs from the perspective of local eHealth designers in Africa. By drawing on their firsthand experiences and lessons learned from working in real-world contexts, the research aims to contribute both to scientific knowledge and practical insights for eHealth designers. Engaged Scholarship was employed through exploratory qualitative research to gather relevant and applicable findings.

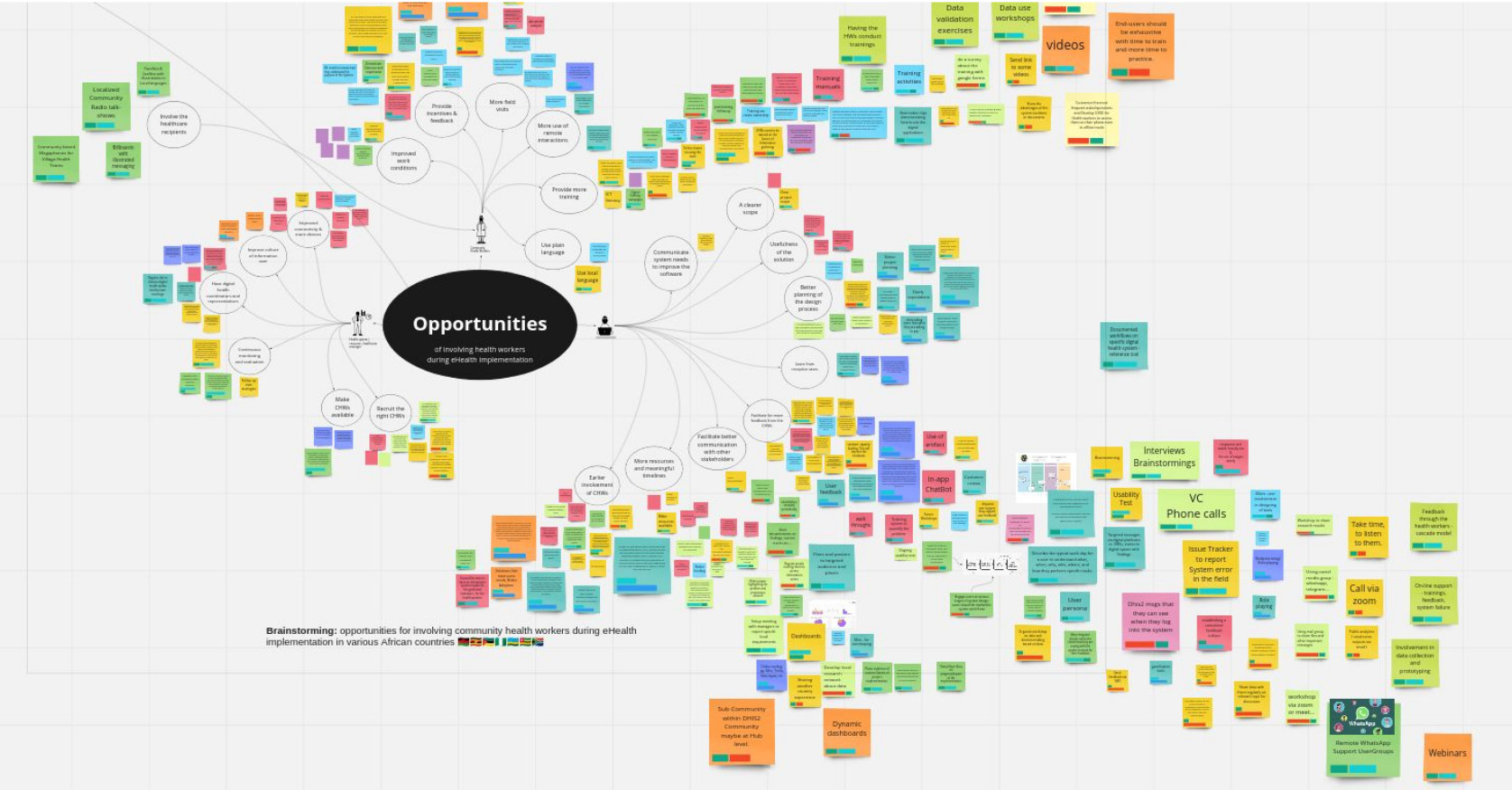

Data collection took place between 2019 and 2022, with limitations due to the COVID-19 pandemic. The collection methods included 4 semi-structured video interviews and 19 remote workshops utilizing online whiteboarding. These workshops involved participants in brainstorming sessions, resulting in 625 virtual sticky notes capturing the practices, experiences, and perspectives of eHealth designers regarding user involvement. The collected data was analyzed, visualized, and presented to participants and researchers from design, information systems, and health systems fields for collaborative analysis. This approach aimed to explore the findings empirically and theoretically.

The research was done as part of the DHIS2 Design Lab which focuses on user oriented design and innovation within the Health Information System Program (HISP), an international action research project coordinated by the University of Oslo. Additionally, the research was conducted in collaboration with the international research project BETTEReHEALTH, which focuses on the digitalization of health services in Africa.

Participants

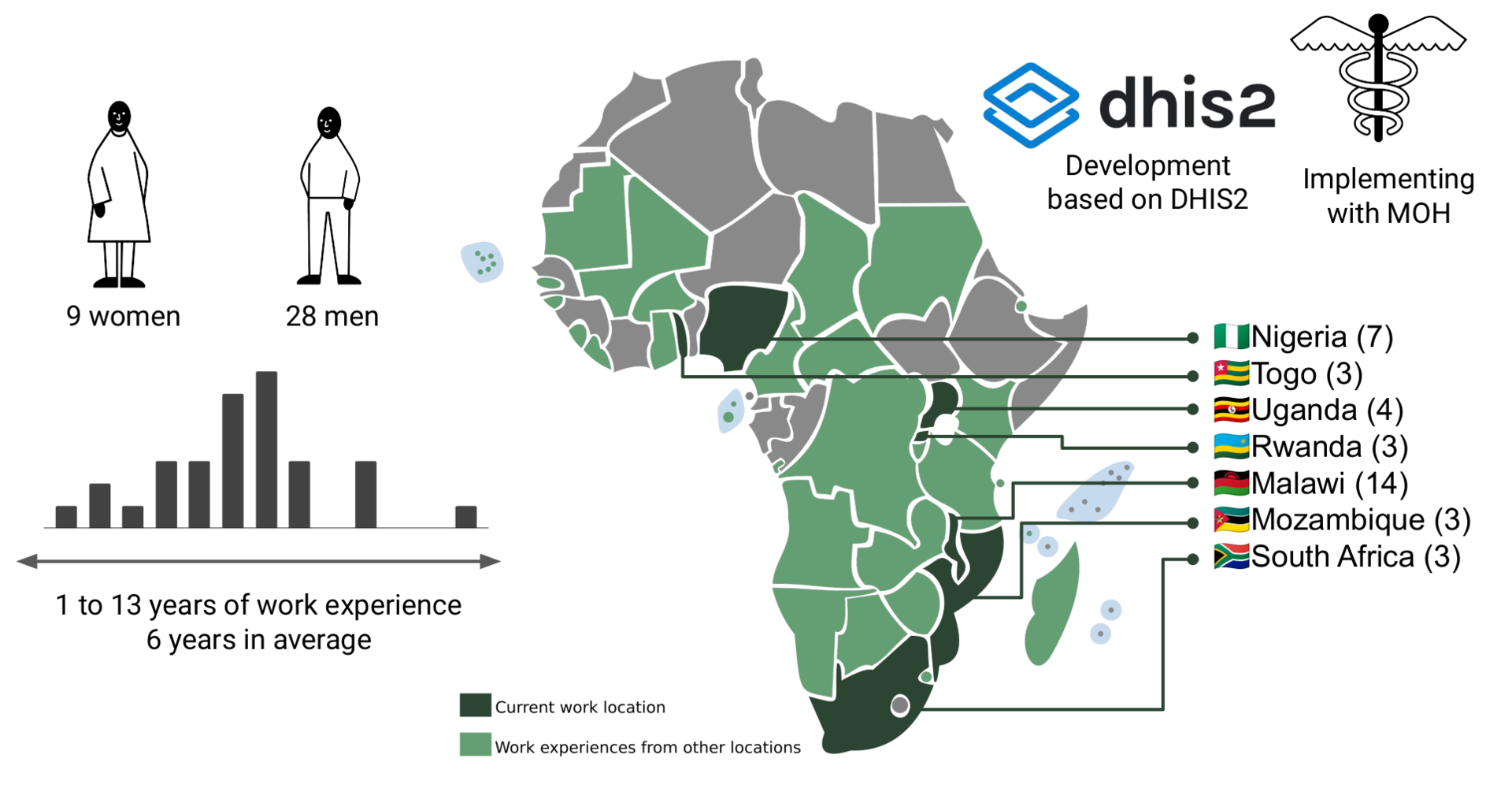

This study involved 37 eHealth designers from seven African countries who have extensive experience in designing and implementing eHealth solutions across the continent. The participants represent diverse organizations including Ministries of Health, universities, international NGOs, HISP nodes, and IT consultancy firms. They primarily develop eHealth solutions using the DHIS2 software and collaborate closely with Ministries of Health to implement these solutions for primary healthcare services at the community level throughout Africa. The participation of professionals from multiple countries and contexts has facilitated the identification of commonalities and valuable lessons.

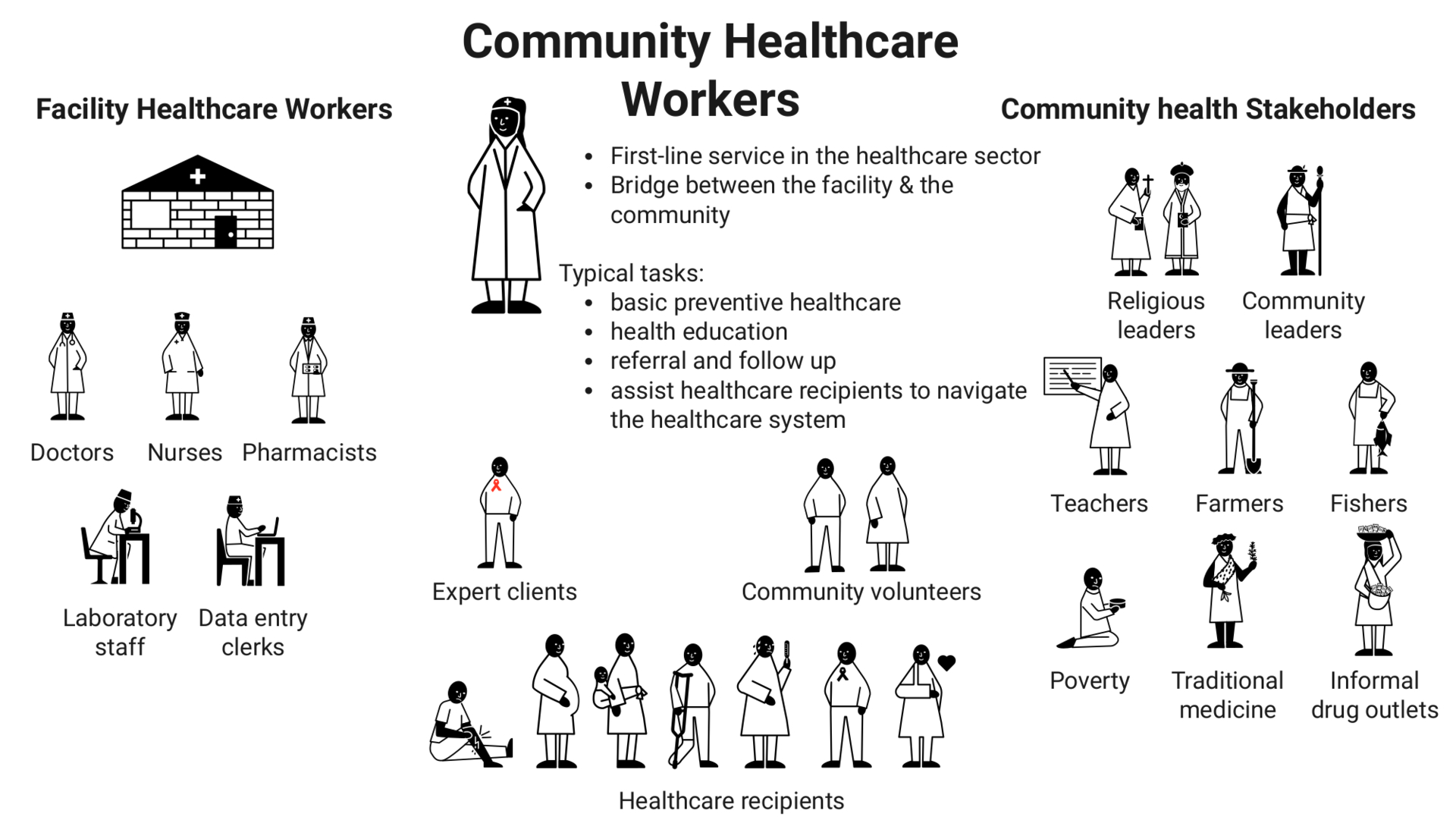

Most eHealth designers in this study have extensive experience working with community healthcare workers (CHWs), who typically have shorter medical training ranging from a week to a year and provide primary healthcare services. CHWs serve as the primary healthcare providers at the forefront, connecting health facilities with communities. They act as gatekeepers to other more specialized healthcare services and often serve as the sole healthcare providers for many individuals throughout the year. These CHWs operate at the lowest level of the healthcare system, often in remote rural areas with limited connectivity and resources. Given their work context, the participants have developed expertise in involving users during design processes within resource-constrained rural communities.

Most eHealth designers in this study have extensive experience working with community healthcare workers (CHWs), who typically have shorter medical training ranging from a week to a year and provide primary healthcare services. CHWs serve as the primary healthcare providers at the forefront, connecting health facilities with communities. They act as gatekeepers to other more specialized healthcare services and often serve as the sole healthcare providers for many individuals throughout the year. These CHWs operate at the lowest level of the healthcare system, often in remote rural areas with limited connectivity and resources. Given their work context, the participants have developed expertise in involving users during design processes within resource-constrained rural communities.

The eHealth designers work practises

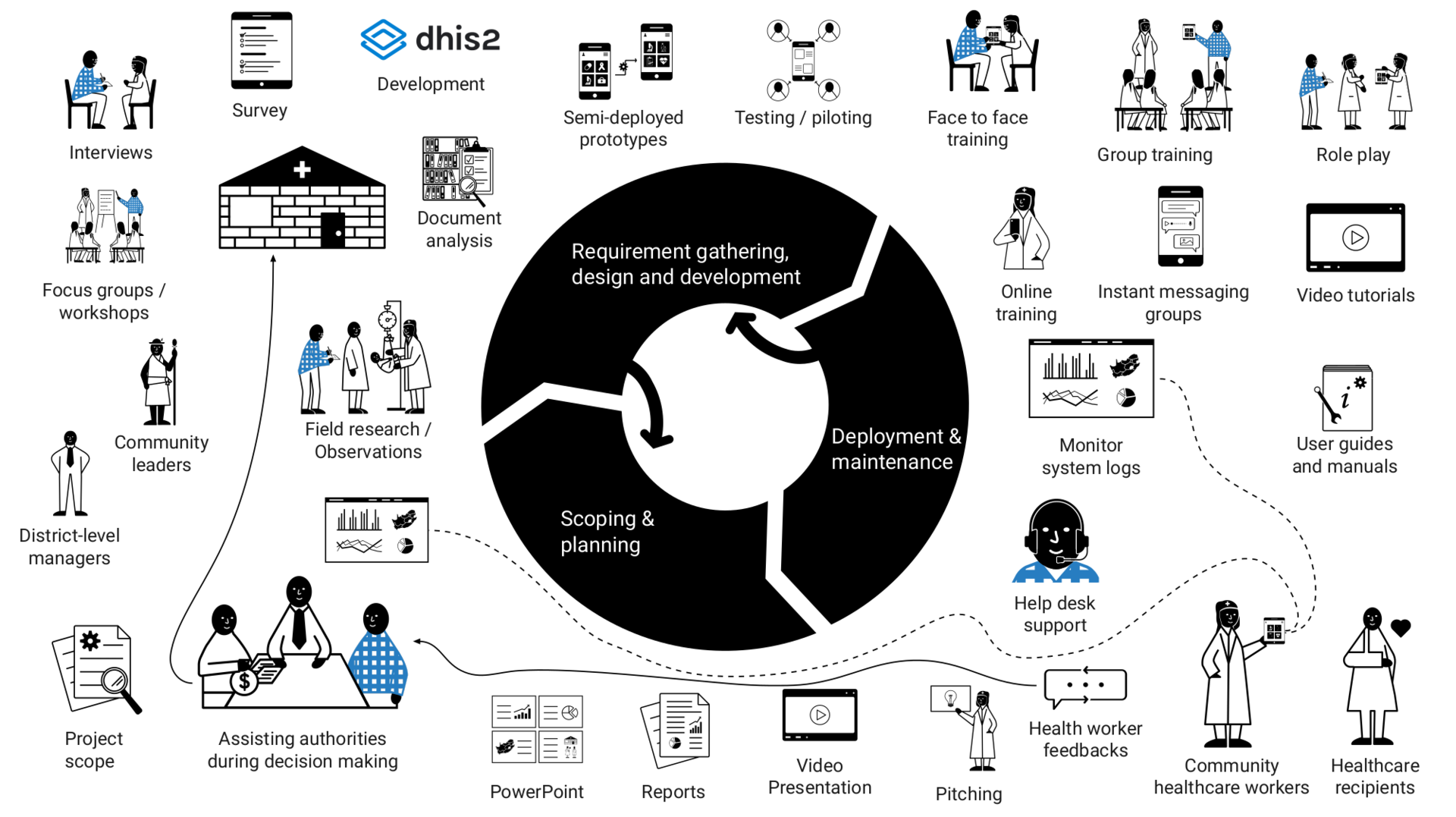

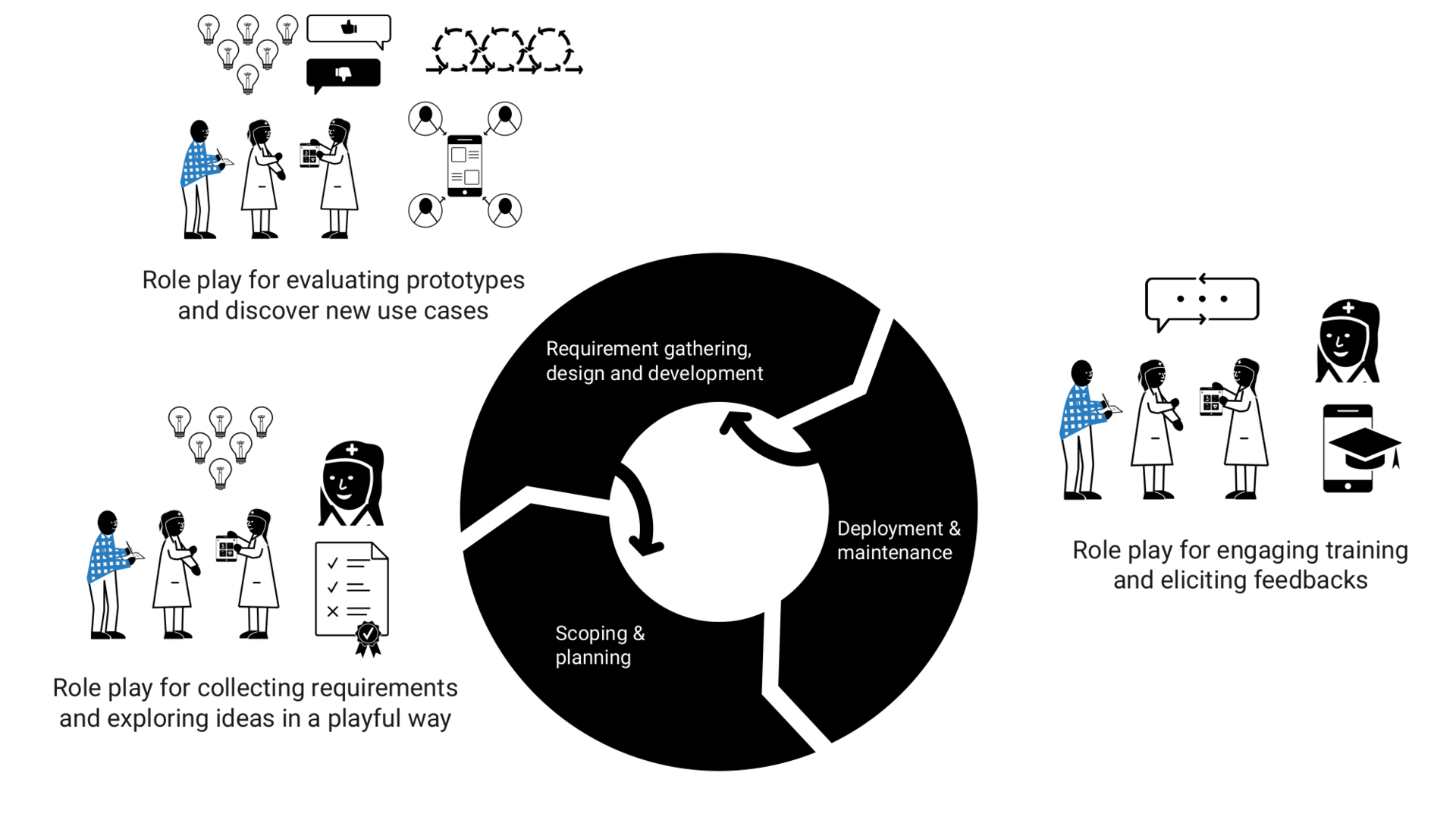

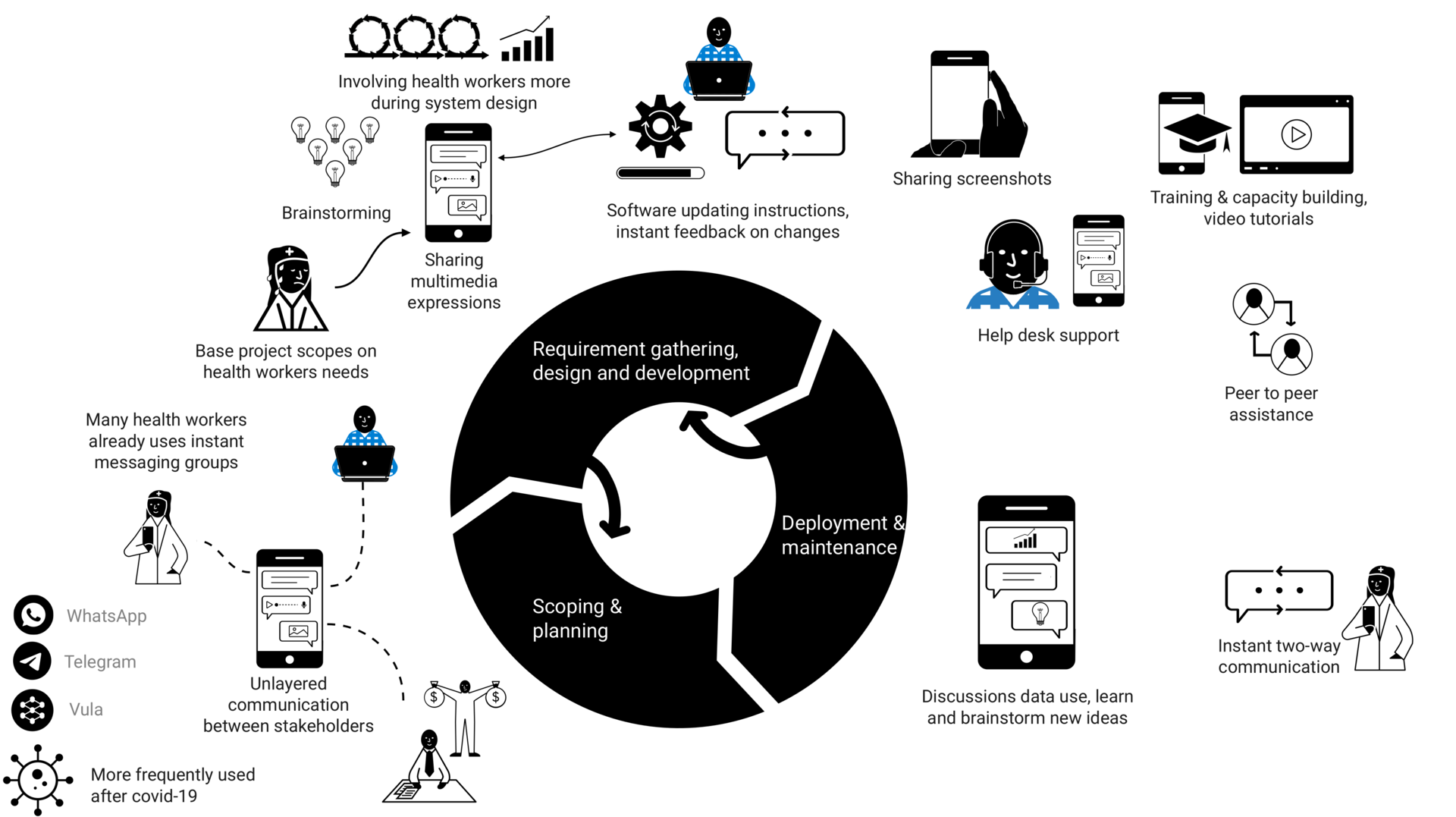

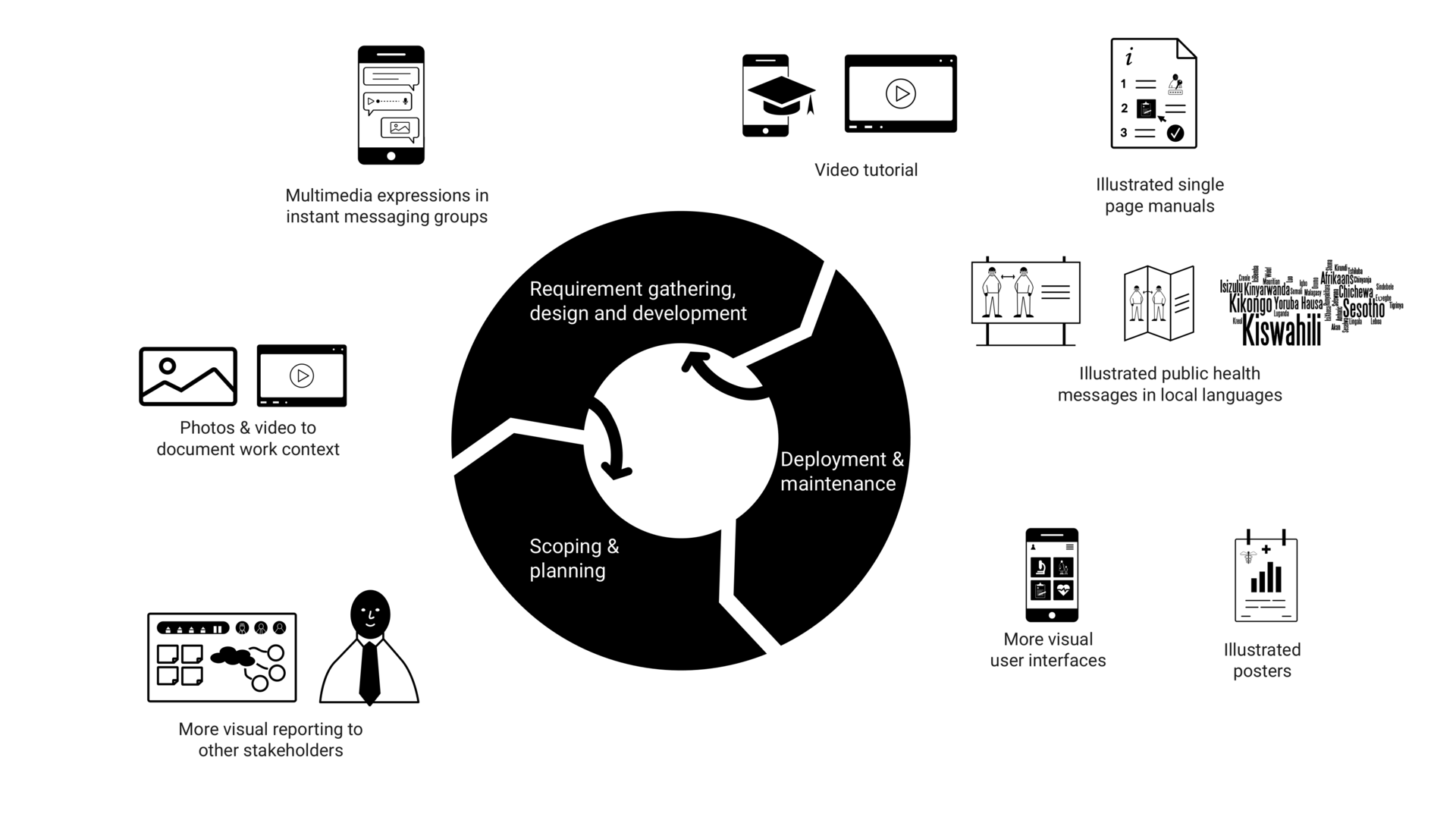

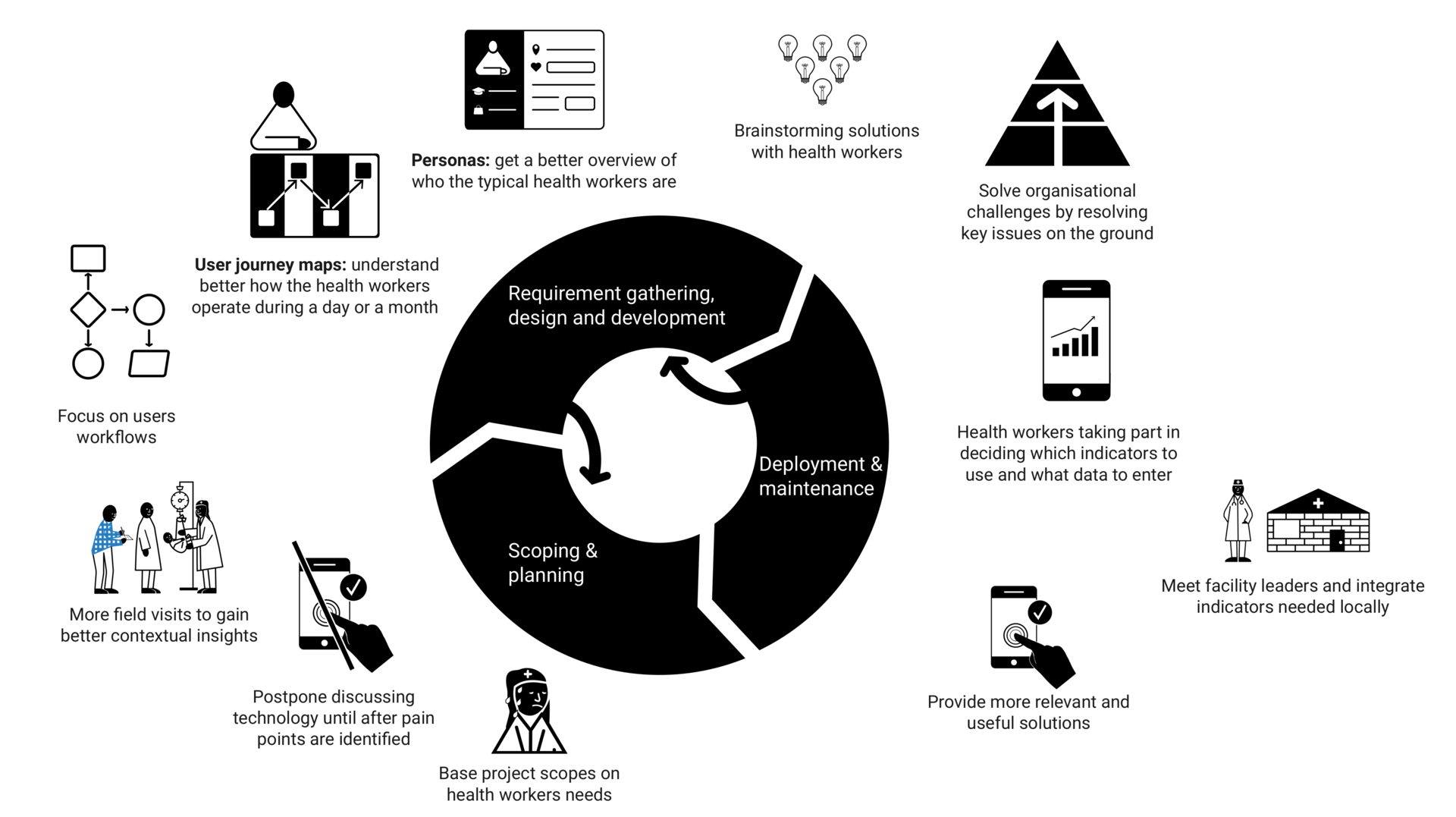

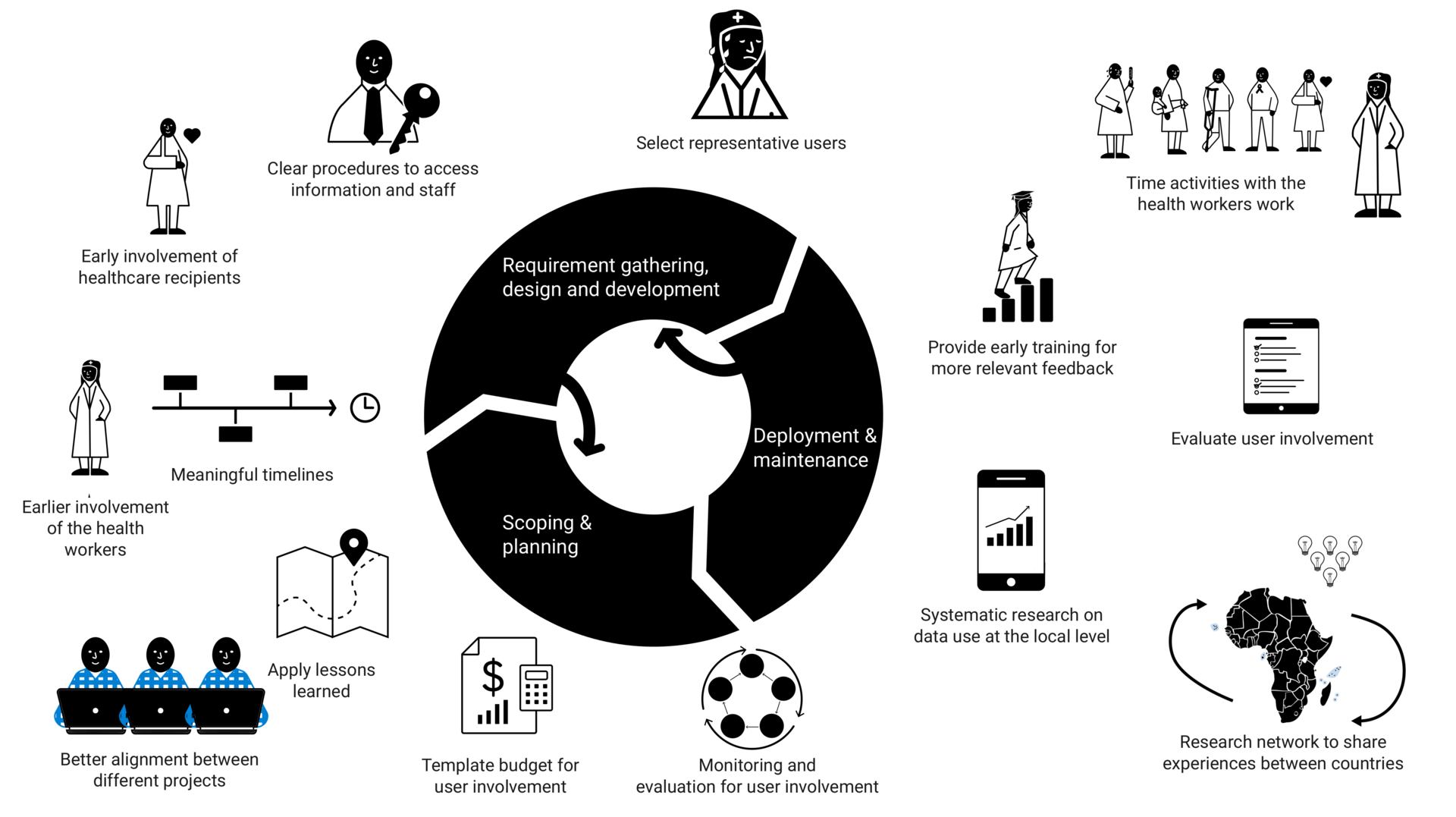

Design and implementation of eHealth solutions is a process which can roughly be divided into three main phases:

- Scoping and planning, where the purpose of the solution and the project plan is determined, primarily by donors and top-level managers. Healthcare workers are, according to the eHealth designers, typically not involved.

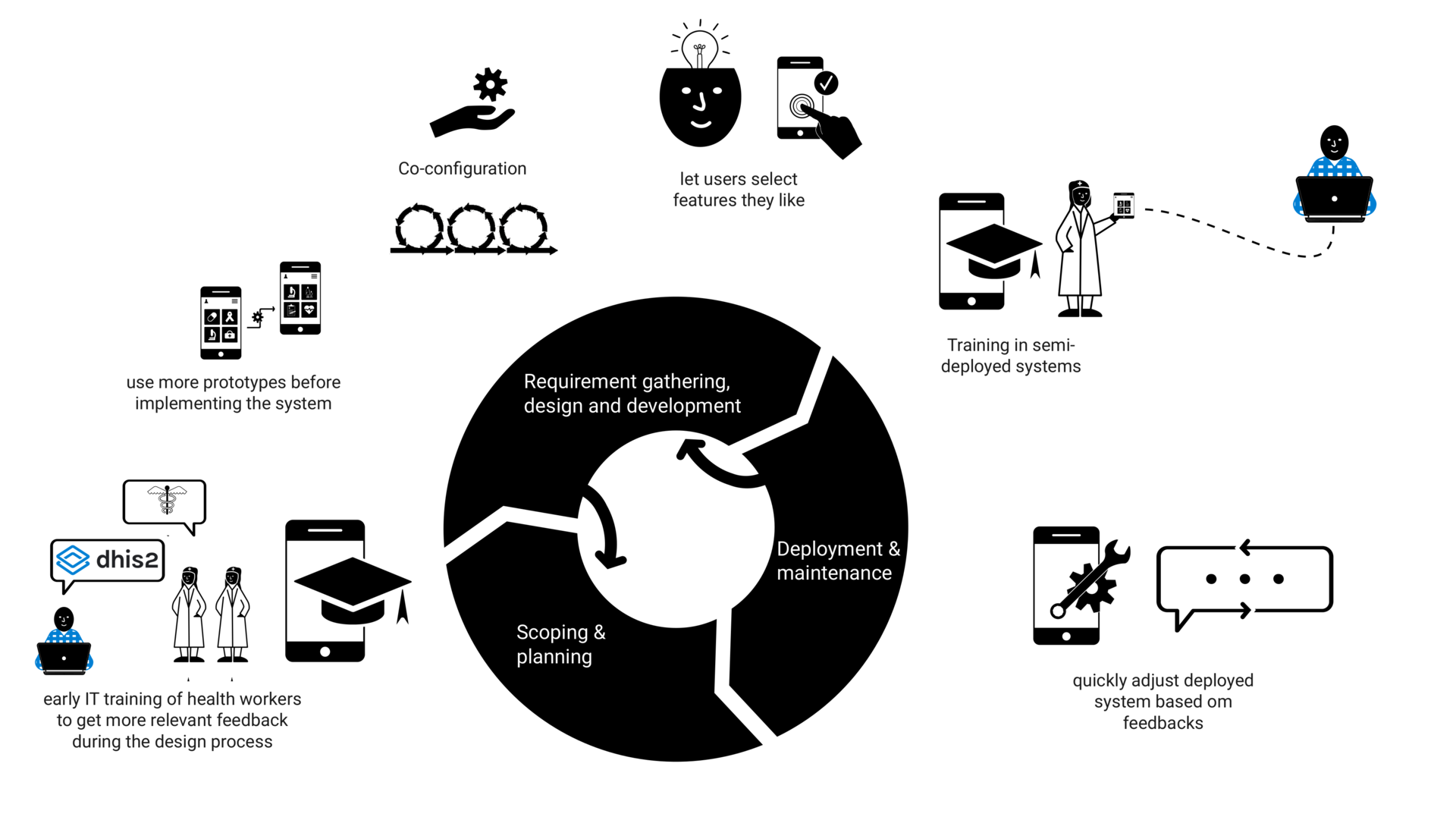

- Requirement gathering, design and development, where the eHealth designers employ various methods such as interviews, field research, workshops, brainstorming, document analysis, and occasionally surveys, to understand the work context of healthcare workers. They also utilize instant messaging groups (IMGs) to maintain remote communication with healthcare workers and other stakeholders. The designers develop eHealth solutions based on generic software, typically DHIS2, and often deploy an early prototype for testing and use in the real environment, gathering feedback from healthcare workers.

- Deployment and maintenance, where healthcare workers receive training, user manuals, user support, and feedback on entered data. Due to the COVID-19 pandemic, eHealth designers have shifted from primarily face-to-face and group-based training to predominantly remote training methods, utilizing video conference tools, IMGs, and video tutorials.

The work process is cyclical, where issues identified during requirement gathering or deployment can lead to renegotiation of project scope, plan adjustments, or new requirements for future systems. The eHealth solutions are designed using generic software packages that have been customized by eHealth designers to fit the diverse contexts of various organizations. This continuous development lifecycle blurs the boundaries between design, requirement gathering, and deployment.

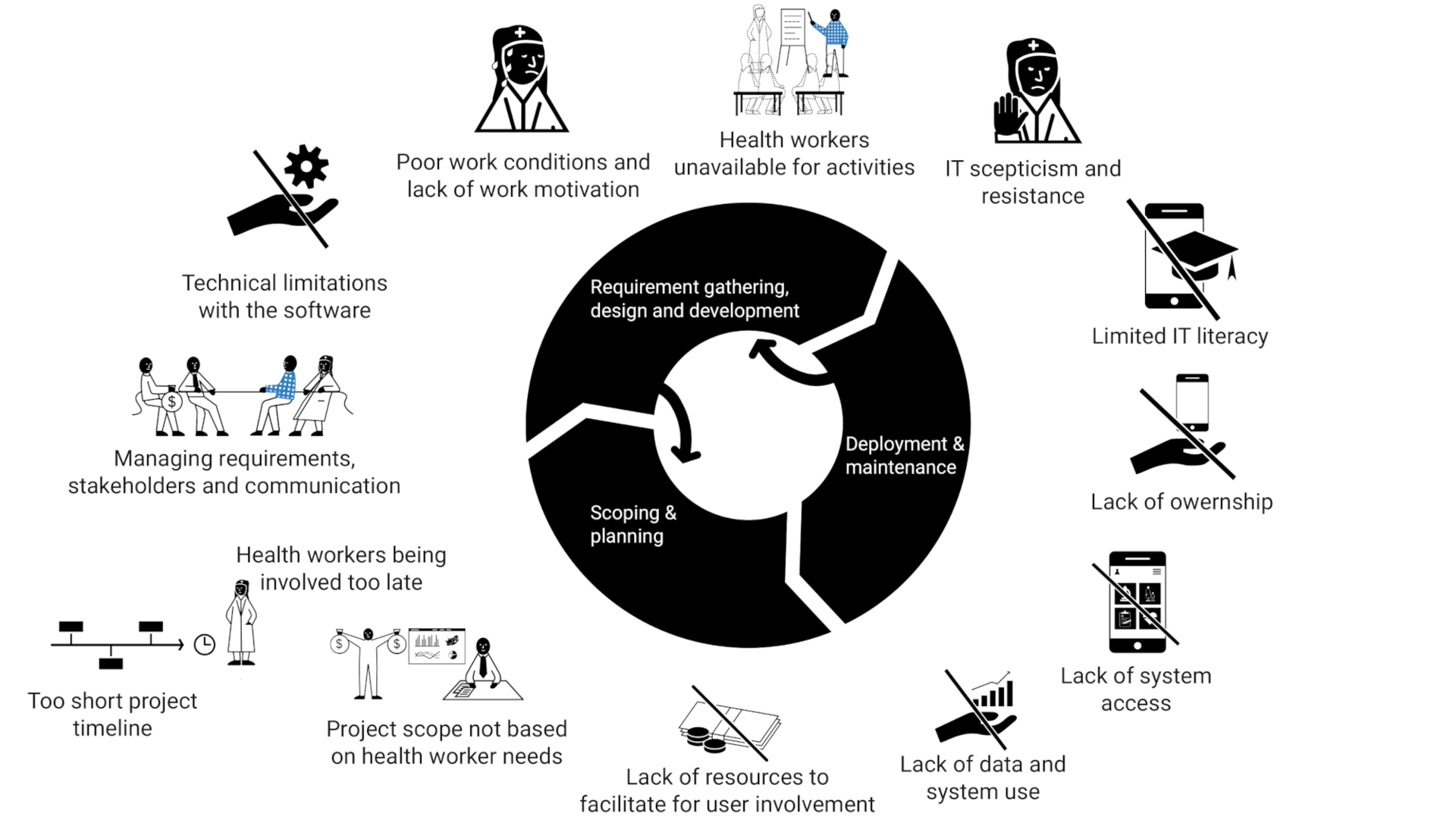

Challenges of involving healthcare workers

The eHealth designers faced challenges in involving healthcare workers properly. One major challenge was the project plan's focus on donor and top-level manager needs, which often resulted in limited time and resources for meaningful user involvement. Feedback from healthcare workers was often received late in the process, making it difficult to implement major changes. The project scope prioritized aggregated data for donors and managers, rather than the needs of healthcare workers, leading to systems that increased their workload instead of supporting their work. Healthcare workers' low pay, heavy workload, and limited IT literacy created skepticism and fear towards IT solutions. Limited IT literacy also hindered their understanding of digital system workflows and ability to provide suggestions for improvement. As a result, healthcare workers lacked ownership of the systems, were reluctant to use them, and avoided activities related to the systems. Limited connectivity and device availability were also frequently reported challenges by eHealth designers.

Opportunities for better involvement of healthcare workers

The eHealth designers proposed various opportunities to enhance healthcare worker involvement. The identified opportunities are not concrete, but represent themes that have emerged through a range of suggestions from the eHealth designers; role play, IMGs, visual methods, design thinking, prototyping with generic software, peer-driven user involvement, effective stakeholder feedback mechanisms, and improved project organization. These opportunities aim to engage healthcare workers through activities for telling, making, enactment, and to support eHealth designers in better structuring of the design and implementation processes.

Role play

Role play is utilized by eHealth designers in Malawi and Nigeria to simulate real-life scenarios where healthcare workers assume different roles, such as healthcare worker and receiver, to solve tasks using technology. It can enhance training sessions, assesses skill acquisition, generates feedback, and discovery of new use cases and requirements. Role play can activate healthcare workers, promoting learning in a fun and engaging manner, and encourages feedback and suggestions. While role play requires minimal equipment, it necessitates travel and on-site interaction with healthcare workers. The eHealth designers see the potential of role play in achieving long-term cost efficiency by involving healthcare workers early in the design process, enabling them to physically explore and evaluate alternative design solutions.

Instant Messaging Groups (IMGs)

IMGs were widely used by participants from all countries in this study to directly communicate with healthcare workers and other stakeholders through remote group chats. Platforms such as WhatsApp, Telegram, and local platforms like Vula in South Africa were commonly utilized. IMGs can serve as an effective way to remotely stay in touch with healthcare workers who were already familiar with such communication channels and had them installed on their phones. It can enable more frequent communication and outreach to healthcare workers in multiple districts while minimizing resource usage. However, in the most rural communities with limited network connectivity and IT skills, IMGs can't be effectively used.

IMGs were extensively utilized for various purposes, including gathering feedback, addressing issues, facilitating group discussions, brainstorming solutions, and providing training materials like video tutorials. They can serve as a means to communicate updates, instruct healthcare workers on system updates, and obtain instant feedback to evaluate healthcare workers experiences remotely. IMGs allowed healthcare workers to share rich multimedia feedback, such as screenshots and voice messages, in an unlayered environment including eHealth designers, managers, and peers. They also promoted peer-to-peer assistance, enabling quick responses and building capacity among healthcare workers, while providing help desk support using less resources. Furthermore, healthcare workers could access the group chats at their convenience and preferred pace.

Visual means

The eHealth designers emphasized that healthcare workers often have a practical orientation and relate better to visual content such as photos, illustrations, and videos. Visual means offer multiple benefits, including allowing healthcare workers to document their work through visual media, and engaging stakeholders by providing rich insights into on-the-ground situations. Visual means are also considered more educational than text, as they enable better training and understanding through illustrations, videos, and more user friendly interfaces. IMGs provide an effective platform for sharing such multimedia content. Visual means reduce user burden and make it easier for users in less text-based cultures to express themselves. However, it is important to note that producing visual content can be more costly compared to text-based content.

Design thinking

The eHealth designers recommended adopting design thinking approaches, which involve healthcare workers early on to understand their challenges and workflows, without focusing solely on technology. Techniques such as personas, user journey maps, brainstorming, and future workshops were proposed to gain comprehensive contextual knowledge and address key problems. However, design thinking is resource demanding and can require significant time commitment from already overburdened healthcare workers. Despite this challenge, design thinking has the potential to alleviate burden for both healthcare workers and organizations in the long run.

Prototyping with generic software

The eHealth designers recommended providing healthcare workers with early insights into how the system works to build capacity and gather more relevant feedback for local design. Using generic software for prototyping enables quicker and resource-efficient creation of functional prototypes, allowing healthcare workers to interact and gain a better understanding of the system's capabilities. The designers proposed involving healthcare workers in selecting solutions and features they are comfortable with. However, presenting only one functional prototype may limit their ability to think beyond the provided solution and explore alternative possibilities.

Using generic software allows for continuous configuration and quick adjustments based on experiences and feedback, engaging healthcare workers and enabling co-configuration of the system. New systems can be semi-deployed as working prototypes to gather feedback from healthcare workers in real-world contexts. However, healthcare workers with limited technology exposure may still find involvement in shaping a functional prototype challenging.

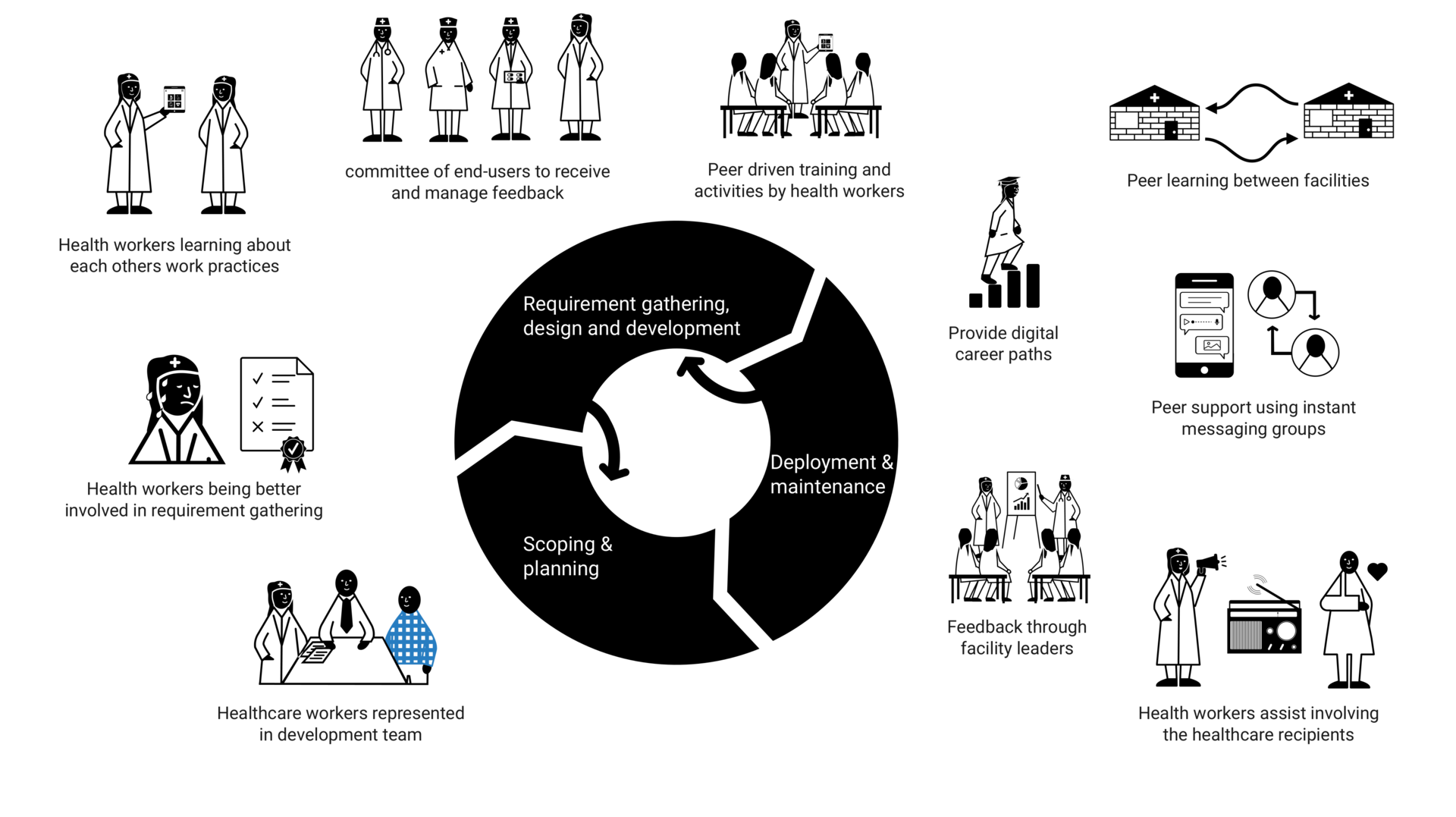

Peer driven user involvement

The eHealth designers proposed granting healthcare workers increased responsibility throughout the design and implementation process. This includes involving them in data collection to prevent design gaps and fostering knowledge transfer at the community level. They suggested establishing an end-user committee to manage feedback and providing healthcare workers with representation in the national implementation team, to facilitate honest feedback through their peers. Furthermore, the eHealth designers recommended involving healthcare workers in peer learning, where they can provide training and support to one another. This approach can promote a blend of medical and digital skills and offers career development opportunities. They also suggested empowering healthcare workers to engage the local community through radio talk shows or megaphones. Peer-driven user involvement has the potential to reduce costs in the long term by shifting tasks to healthcare workers, but it may require initial investments and potentially burden the healthcare workers with more work tasks.

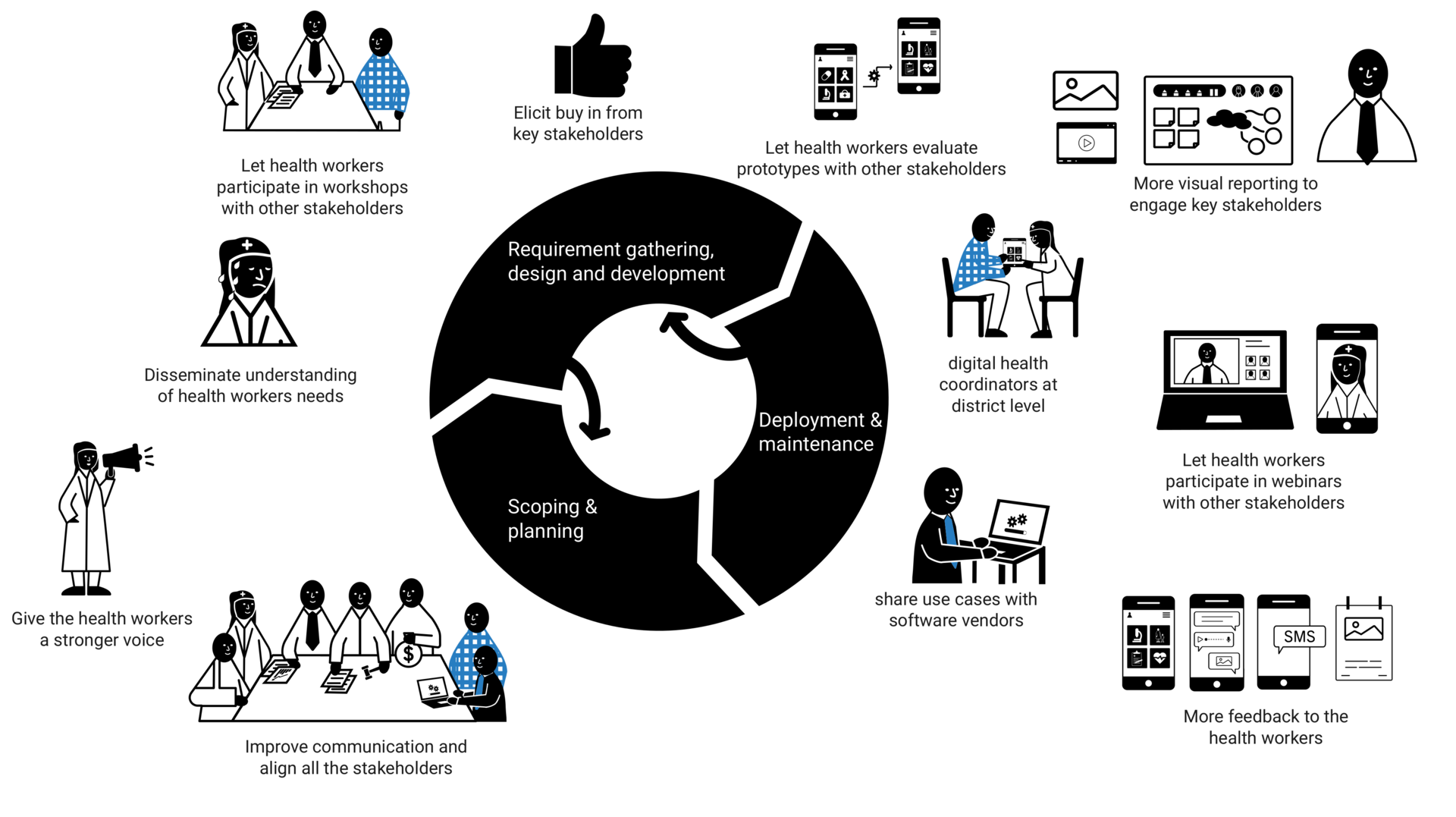

Effective stakeholder feedback mechanisms

To improve communication and understanding between healthcare workers and key stakeholders, the eHealth designers proposed enhanced stakeholder feedback mechanisms. This can involve establishing networks of digital health coordinators at the district level, providing photo and video documentation informing stakeholders about about ground-level needs, and facilitating better communication with software vendors. These mechanisms can have the potential to attract resources where they are needed. Additionally, involving healthcare workers in workshops alongside other stakeholders, providing healthcare workers regular updates and feedback, and expressing appreciation for healthcare workers participation, were suggested as ways to foster engagement and effective collaboration.

Improved organizing of projects

The eHealth designers proposed improving the organizing of projects to enhance user involvement. These include better alignment of design projects, allocating adequate budget and time for healthcare workers participation and implementing a monitoring and evaluation system for continuous improvement and knowledge sharing among different countries. They also emphasized the need for improved access to information and staff, involving healthcare workers earlier, and better timing of activities with healthcare workers' schedules.

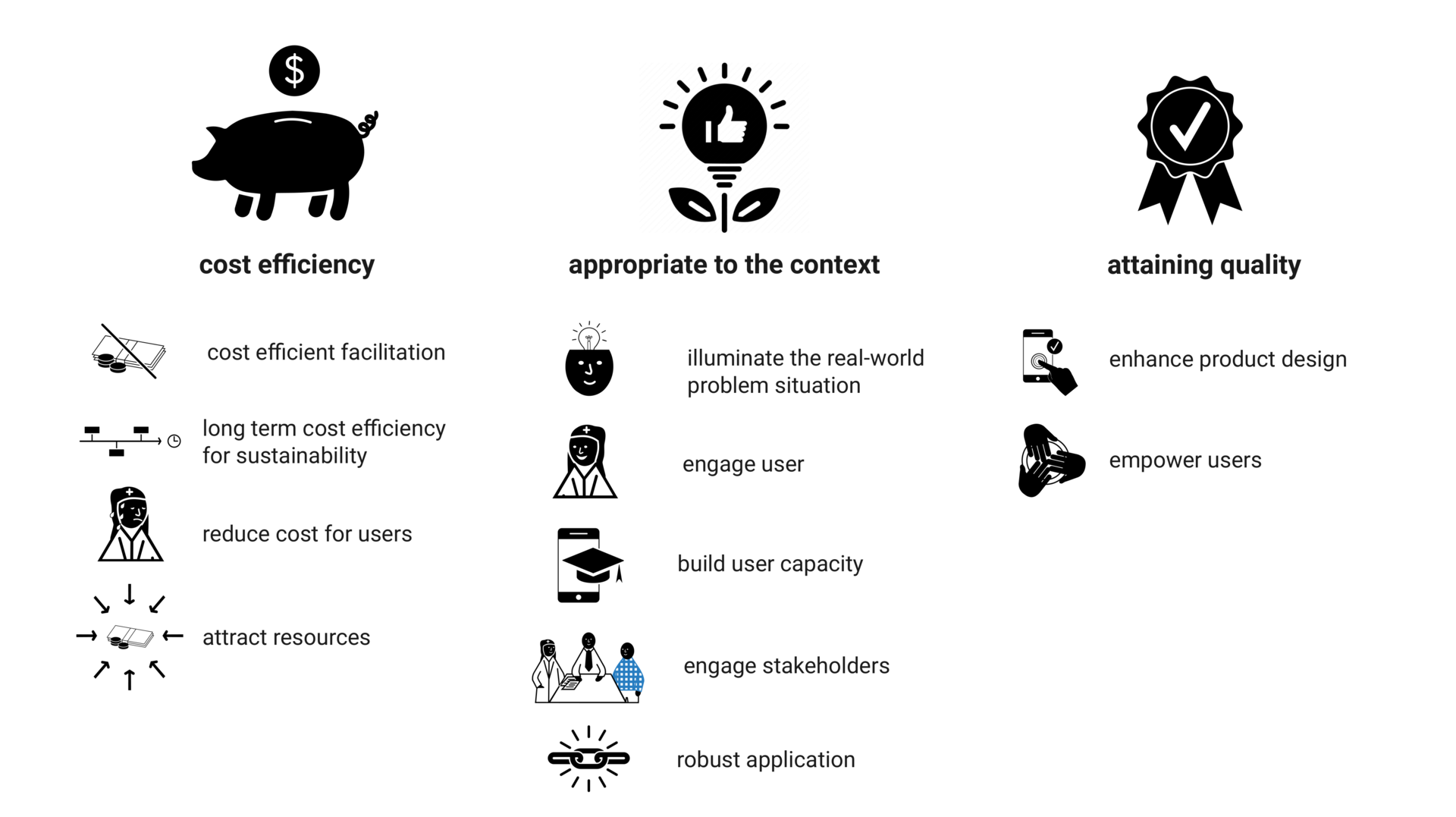

Balancing cost efficiency, appropriateness to context and quality

These opportunities share traits of context appropriateness, cost efficiency, and improving the quality of user involvement, and can potentially address some challenges of involving user in LMICs. However, each opportunity involves trade-offs balancing these factors in various ways. Cost efficiency can be considered from the perspective of the designers, the user organization, the users, or be improved by attracting more resources. Appropriateness to the context can involve illuminating real-world problems, engaging users and key stakeholders, building user capacity, and being robust in application. Quality can entail both enhancing the product design and empowering the users.

All opportunities have long-term cost reduction potential for user organizations, but visual means, design thinking, and peer-driven user involvement may not be cost-efficient for eHealth designers in the short term. Design thinking and peer-driven user involvement can also increase the burden on users in the design process. Limited resources and heavy work burdens in LMICs indicate that options lacking immediate cost efficiency for designers and reducing user burden may be less viable.

Reducing costs can compromise context appropriateness and quality of the result, creating tension in frugal user involvement. Context-appropriate, face-to-face methods empower users to express needs in their natural language and lowering threshold to give honest feedback, but require more resources. Sparse remote approaches can be cost-efficient for the eHealth designers and less burdensome for the healthcare workers, but limit contextual knowledge, depth of involvement and developing trustful relationships. Combining remote and on-site involvement can be crucial to balance constraints and benefits.

Role play and IMGs can offer high-quality user involvement in different ways. Role play allows for face-to-face exploration and assessment in a realistic setting, suited for contexts with predominantly oral and embodied communication. IMGs, used in all participating countries, offer remote involvement and support many of the other identified opportunities such as peer-driven user involvement, visual means, prototyping with generic software and effective stakeholder feedback mechanism. IMGs can therefore probably be considered as an archetypical means of frugal user involvement. One important lesson learned from both role play and IMGs can be to build on the existing cultural, social and technical infrastructure within the context as a strategy to provide cost efficiency yet appropriate forms of user involvement.

Acknowledgement

Thank you to my supervisors Magnus Li and Jens Johan Kaasbøll, the DHIS2 Design Lab, the HISP-community, as well as the BETTEReHEALTH project, for providing a very conducive research context for this study, as well as all the 37 participants from the participating organizations: University of Malawi, Cooper Smiths, HISP Malawi, HISP Nigeria, HISP Rwanda, HISP South Africa, HISP Uganda, HISP West and Central Africa, and Saudigitus. In addition I've received valuable feedback from researchers at the Health Department of SINTEF Digital and the DESIGN research group. I would also like to appreciate the graphic designer Persia Duncan, and the community healthcare workers Charles who opened up and let me stay in his home and experience life in a rural community in Malawi.